the Langstons of Laurens

Thomas Smith Langston and his second wife Molly Wharton

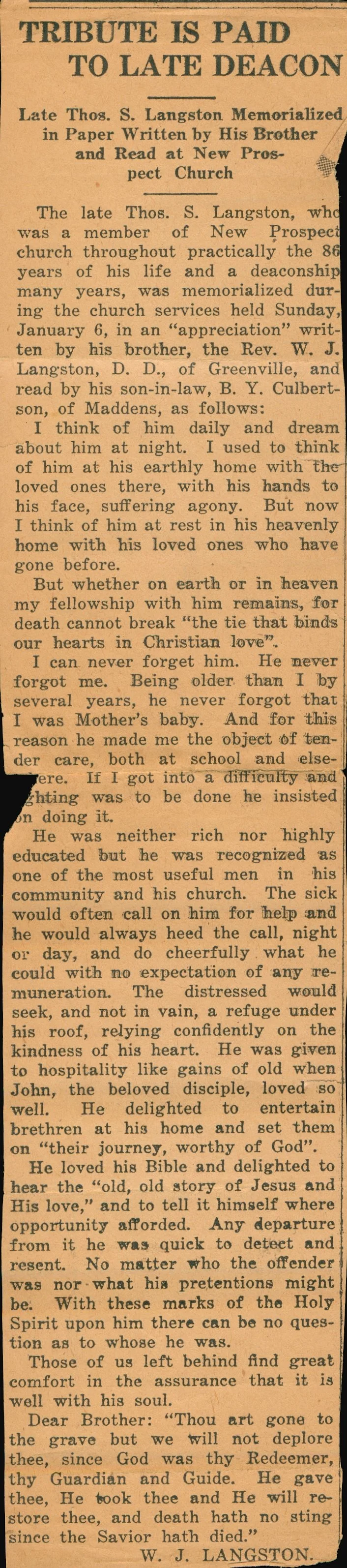

Thomas Smith Langston was the guy you went to if you needed a tumor removed. He was self-taught in medicine; Skip called her grandfather a country doctor. He was often called by neighbors to help deliver babies. And he had a remedy for treating cancerous tumors that involved taking folks out behind the barn and pouring pot ashes, or lye, on the lesion until it was burned away. It’s no coincidence that two of Thomas Smith Langston’s grandchildren would enter the medical profession half a century later.

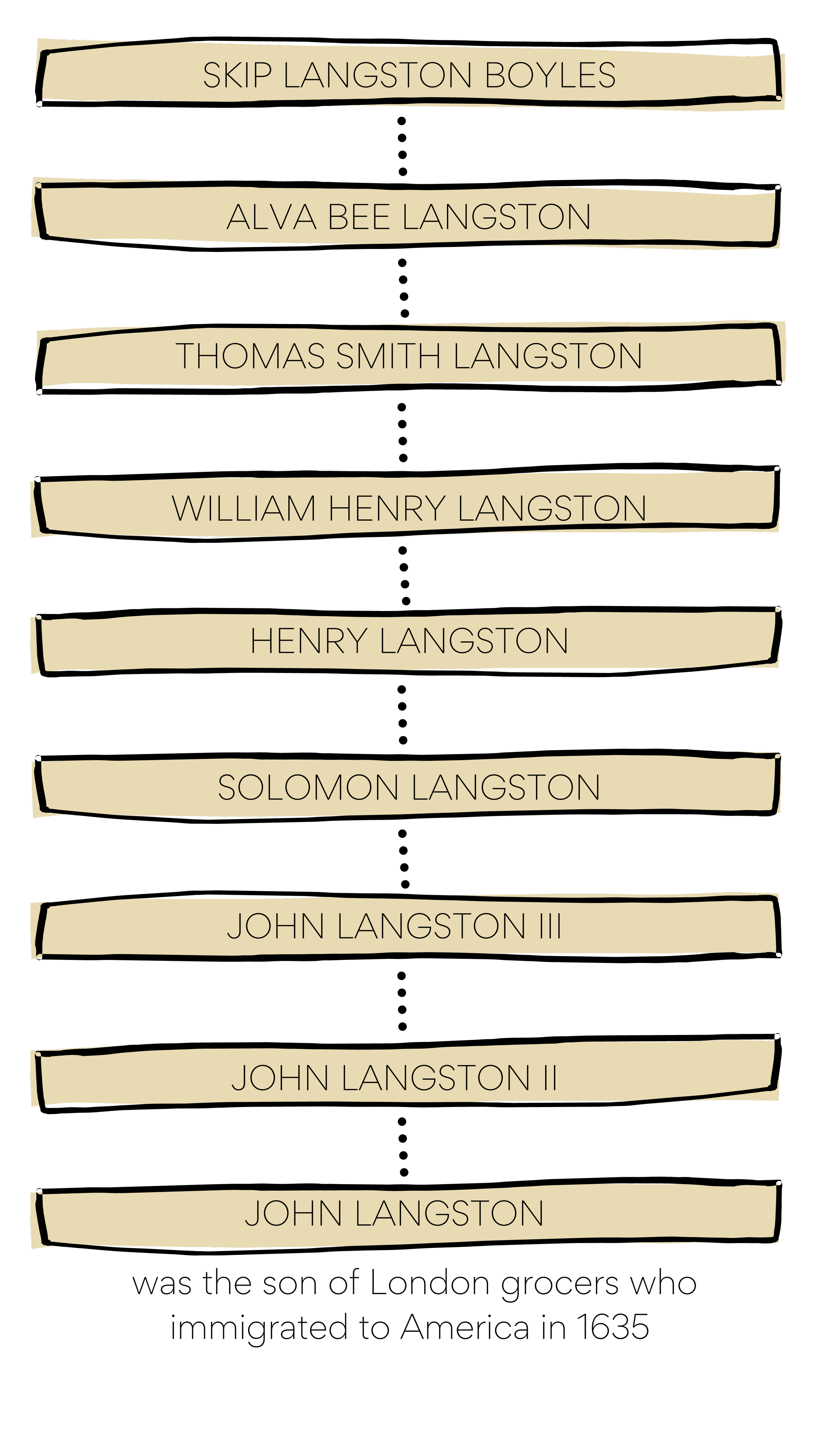

Thomas was just one of twelve generations of Langstons in this country, making the Langston line our oldest family line. John Langston I was the first—leaving his home in England at age fifteen in 1635. The son of a London grocer, John Langston indentured himself to a rich man and came to the Jamestown area to work off his debt. Indentured workers in Virginia were generally able to work their way free in about five years, and they often received fifty acres of land to help them get established afterwards. With that kind of support, John eventually was able to purchase over a thousand acres in New Kent County, just north of Jamestown, becoming a moderately wealthy landowner.

In 1676, John Langston became a key figure in Bacon’s Rebellion. In what is often seen as the first stirrings of the Revolution, landowners like Nathaniel Bacon wanted the royal governor to remove the neighboring indigenous Doeg people to free up more land for European colonists. Bacon formed a militia, but when he unexpectedly died months later, John Langston I was one of a handful of men to lead the offensive. In the end, the Governor ordered several of the prominent leaders of the rebellion hanged. John Langston I somehow escaped. He was officially pardoned in January 1680, but when he was elected to the House of Burgesses in Virginia soon afterwards, he was barred from holding public office due to his part in the rebellion. The legacy of John Langston I’s alliance with Nathaniel Bacon continues for several generations. There are historians that have noted the prevalence of the name Nathan in the Langston family (and conversely, the name Langston in the Bacon family) for the next two centuries. In the aftermath of the rebellion, John Langston I left the Jamestown area and started the southward migration that would, in the lifetime of his grandson John Langston III, lead the Langstons to Laurens, South Carolina.

With the first John Langston, we see the beginning of the Langston family’s involvement with slavery. John’s wife wife Katherine Mulford enslaved two people in 1694: Tony and Mingo. Her husband John passed away sometime before 1694, and it could be that she felt she needed the help. There very well may have been others enslaved as well. Their son, John Langston II, enslaved eighteen people on his plantation called Saram. His son, John Langston III, would mention nine enslaved people by name: Harry, Lamkin, William, Benn, Venus, Ede, Tim, Peter, and Hippoh. According to family lore, Ede lived to a 112, and had been blind for quite some time. But just before she died, she regained her eyesight and said she could just see the button’s on “Marse John’s vest”, who had been dead for years at this point.

Living in upcountry South Carolina didn’t mean the family could skirt the American Revolution when it came. Solomon Langston, son of John Langston III, would serve in the Spartan Regiment. And it was during the Revolution that Solomon’s fifteen-year-old daughter, Dicey Langston, would take her famous stand to protect her family. The story goes that she overheard loyalist plans to attack her brother James and other neighbors, so she ran four miles in the dark of night, crossing a rain-swollen river, all without the aid of a lantern or a horse, in order to warn them. Thanks to her bravery, her brother and neighbors managed a harrowing escape. In a separate encounter, she prevented Loyalists from shooting her father Solomon by standing between him and the gun. The attackers were so moved by her courage that they called off the raid. There is now a monument on the side of the road in her honor in Traveler’s Rest, South Carolina. You can see this memorial and read more about Dicey here

Dicey’s father Solomon Langston was already middle-aged when the Revolutionary War broke out. He served a short stint as a lieutenant in the local militia, and at the end of the war, settled back into running his property near Laurens. He would later donate much of the land to the Langston Baptist Church, which still has an active congregation to this day. Solomon was quite wealthy, and enslaved at least twenty-nine people to grow his cotton, corn, tobacco, sheep, hogs, and cattle. One of Solomon’s son, though, Hiram Bennett Langston, bucked the family livelihood and eschewed slavery. He is the only Langston we have record of denouncing slavery. By 1810, Bennett freed his people, sold his plantation, and moved his family to Indiana which had just become a new territory of the United States. What sparked this lone act of abolitionist consciousness, we have no record.

Our family line doesn’t pass directly through Dicey or Bennett, however, but through their brother Henry Langston. Between Henry Langston and Alva Langston, there are just two generations: William Henry Langston and his son Thomas Smith Langston, the country doctor. In 1789, Henry married Sarah Murphy— our family’s most recent immigrant to America. Sarah had left her home in Belfast, Northern Ireland, when she was just seven years old, and came to America with her Gaelic-speaking parents in 1776. Her family had astounding timing arriving to a country in revolutionary turmoil.

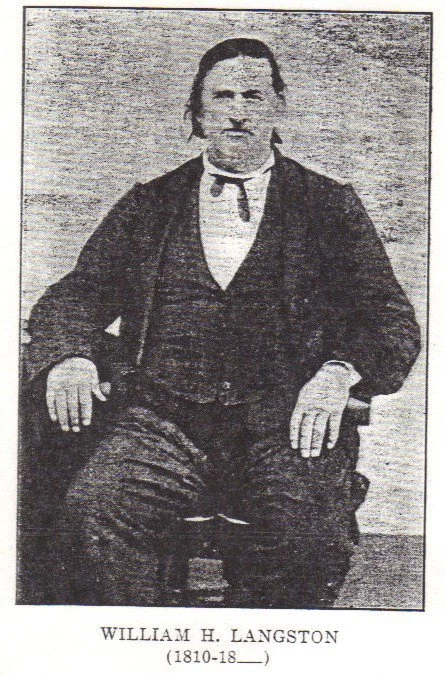

Sarah Murphy Langston owned at least four slaves herself, somewhat atypical for women in those times. Her husband Henry Langston owned at least four more enslaved people as well; one we know was named Adam. Henry and Sarah’s son, William Henry Langston enslaved thirteen people. He was a prominent member of New Prospect Baptist Church, where several of our Langston relatives are buried. He served as probate judge in Laurens for decades, and the only remaining picture we have of him shows a man of stern judicial mien. He served as a private in the Confederate army, as did his son, Thomas Smith Langston, the father of Alva.

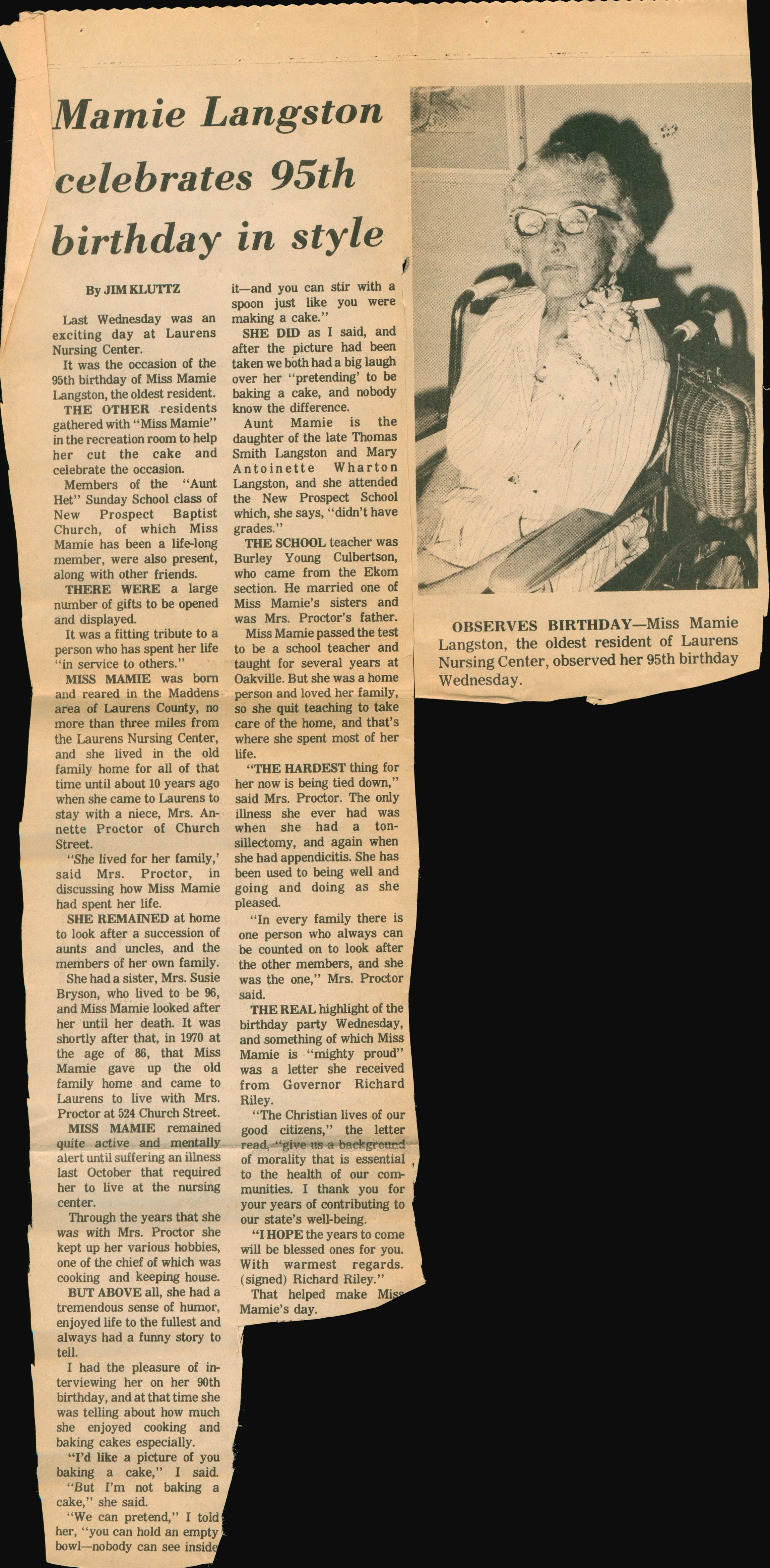

The side that Thomas Smith Langston fought on in the Civil War was defending a practice of slavery that ran in the Langston family for seven generations. Thomas himself never enslaved people; he was too young. Regardless, he grew up in a world premised on this wealth and privilege. His children all had access to higher education, even his daugthers, at a time when most didn’t. Two of his children, Mamie and Carrie, became educators themselves. His son Alva attended seminary and became a missionary. Alva’s twin sister Alma married a church historian. This long-running involvement with enslavement had a role in shaping this branch of our family tree even generations after Emancipation.

Map of Laurens County during Thomas’ lifetime. You can see “T S Langston” off the main road south out of downtown Laurens

Tip: You can click on each photo to enlarge and read details. If you download the image, you can see it at even higher resolution.