A collection of work examining the family stories that White Americans tell and choose not to tell about their origins in this country

-

When I told a family member that I’d found records showing our ancestors had enslaved people, they quickly said “no”—and then, after a pause, insisted we would surely know if they had. That knee-jerk response launched this entire collection.

These pieces trace my journey sprawling three states—North Carolina, South Carolina, and Kentucky—from that moment of family denial through old estate documents and Civil War letters, and eventually into dream conversations with the ancestors. Using traditional techniques, church banner reimagined from my Southern Baptist childhood, and worn textiles I’ve found and mended, I’m exploring how White families maintain silence while continuing to benefit from enslaved-generated wealth.

The work moves from confronting hard evidence to trying to communicate with ancestors—through imagined conversations, dream work, and AI that animates old family photos. I’ve sewn dozens of dolls representing ancestors and piled them awkwardly into a too-small bed with myself. I’ve embroidered questions to my great-grandfather and slept with them under my pillow, waiting for answers that came so intensely I had to retire the piece as an oracle after just three nights.

This collection emerges from a belief that our ancestors might still have work to do—and that we might be the ones meant to help them do it. Like other artists examining inherited trauma and unaddressed histories, these works suggest that the past isn’t finished with us yet. Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s Unburied Sounds shows us that American bombs still lie undercoated in the soils of Vietnam even today; similarly, the legacies of slavery continue to shape our domestic landscape in ways some of us are only beginning to understand.

Rather than ending with revelation, the work culminates in active repair: both the literal mending of a found quilt and the ongoing spiritual work of ancestral accountability. This joins broader conversations about reparations by asking not just “what did our families do?” but “what do the ancestors need from us now?”

100% of proceeds from sales support scholarships through the Thurgood Marshall College Fund, providing students with opportunities at historically Black colleges and universities across the country—making the repair work concrete and immediate.

THE COLLECTION

LIKE FAMILY

In 2019, I visited this family burial ground in South Carolina, where my white ancestors rest under elaborately carved tombstones while sunken graves marked only with rough fieldstones likely hold the people they enslaved. Outside the cemetery walls, I found even more unmarked graves, which made me think about how even in death, the rules of whiteness attempt to determine who gets remembered and how.

GENERATION

This quilt was made by my partner's great-great grandmother, Cora Belle Eisenbise of Sabetha, Kansas, using an old chenille bedspread as batting instead of traditional cotton. Over the years, the chenille has worn through the patchwork, creating this ghostly pattern of abrasion in the quilt. I've covered the whole piece with black silk chiffon, like redacting a document, because something about those worn-out places reminds me how decisions from long ago keep re-surfacing in our present lives.

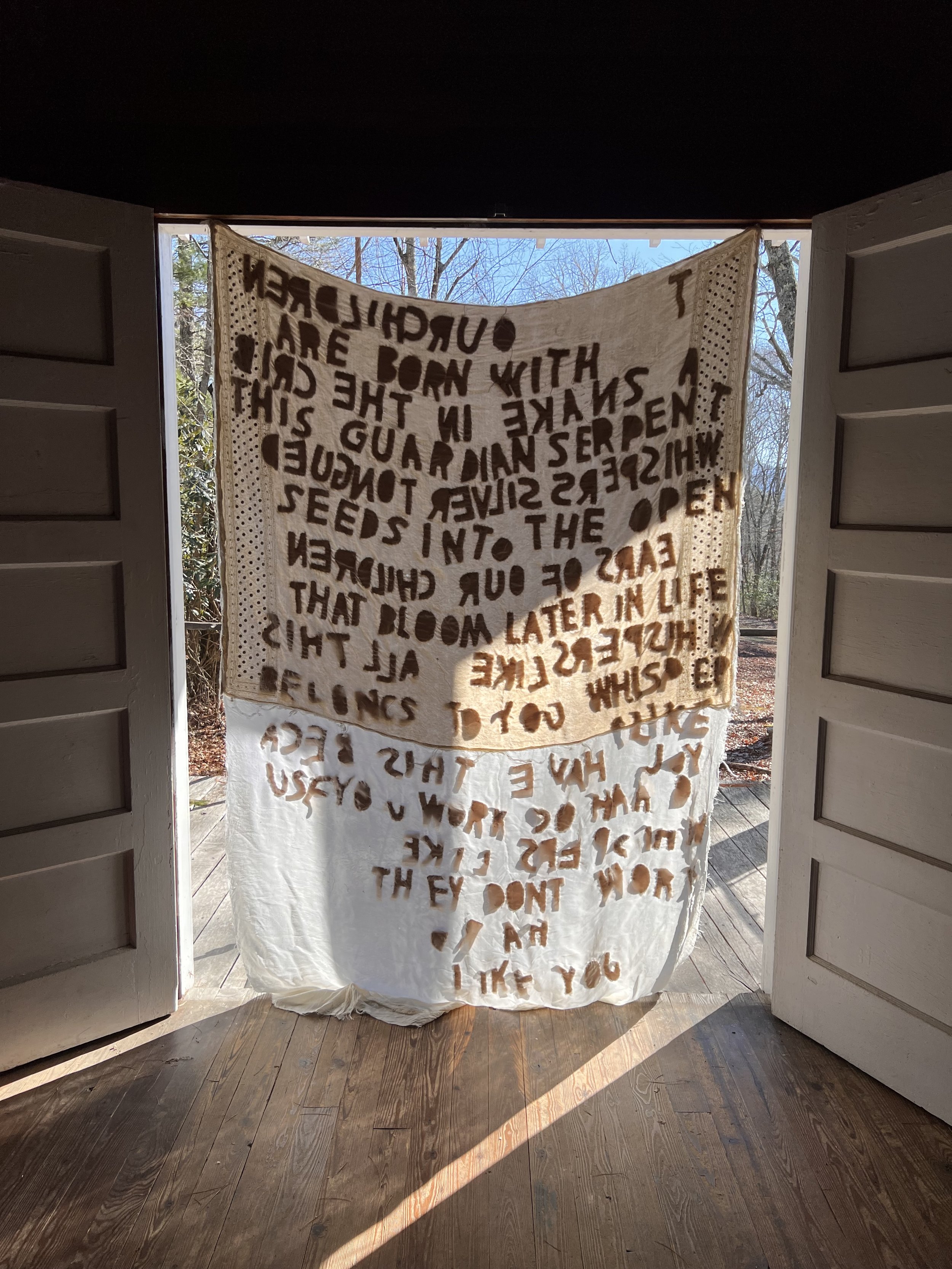

OUR CHILDREN

I created this piece exploring how ideas around race get passed from one generation to the next. It's written using an ancient writing pattern called boustrophedon where each line picks up directly under where the previous one ends, creating a serpentine path that mirrors how these inherited messages wind their way into us before we're old enough to question them. Following the text with your eyes becomes part of the experience—you trace the same winding journey these messages take as they work through generations.

Text: our children are both with a snake in a crib this guardian serpent whispers silver tongued seeds into the open ears of our children that bloom later in life whispers like all this belongs to you whispers like you have all this because you worked so hard whispers like they don’t work hard like you

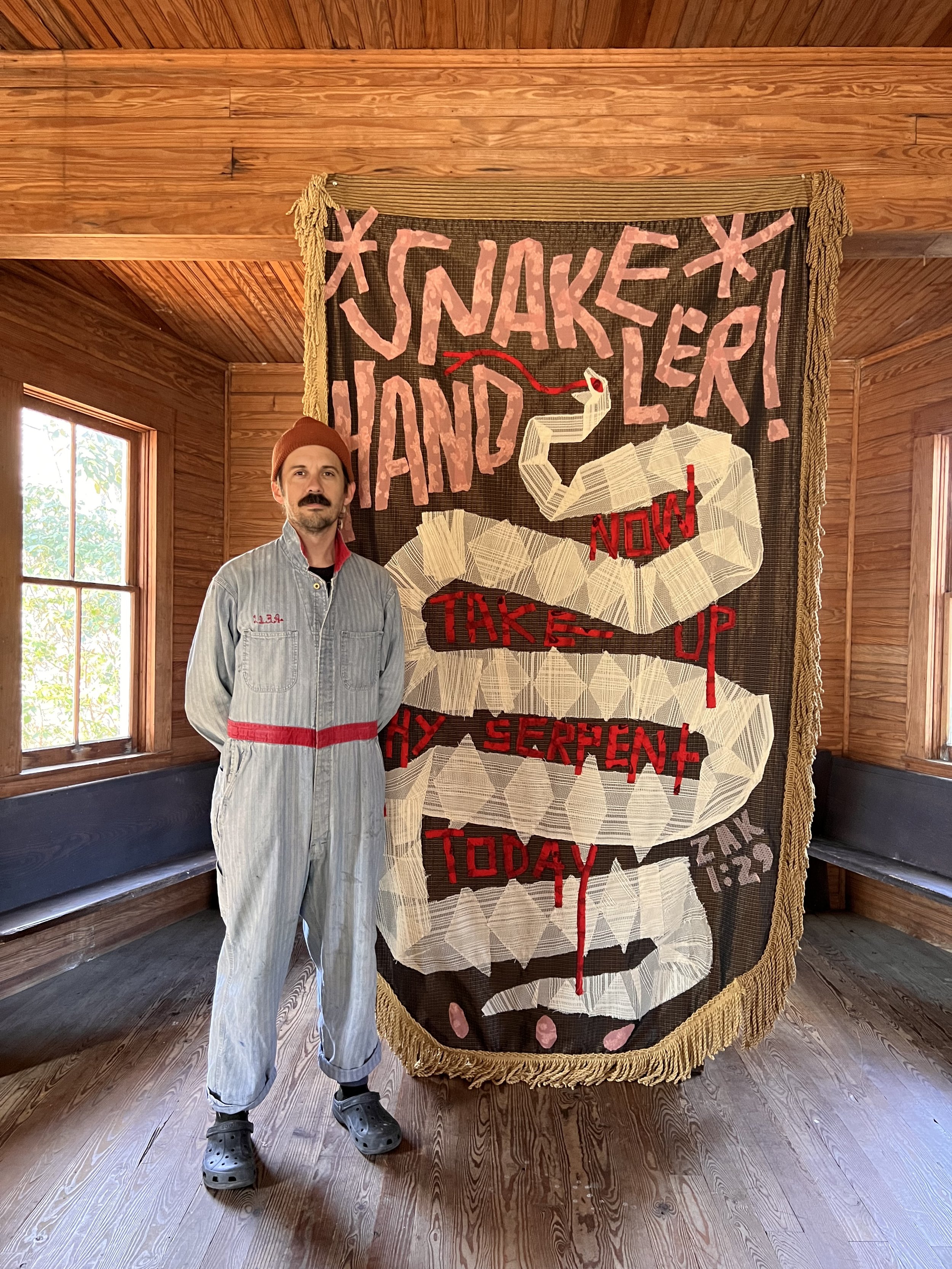

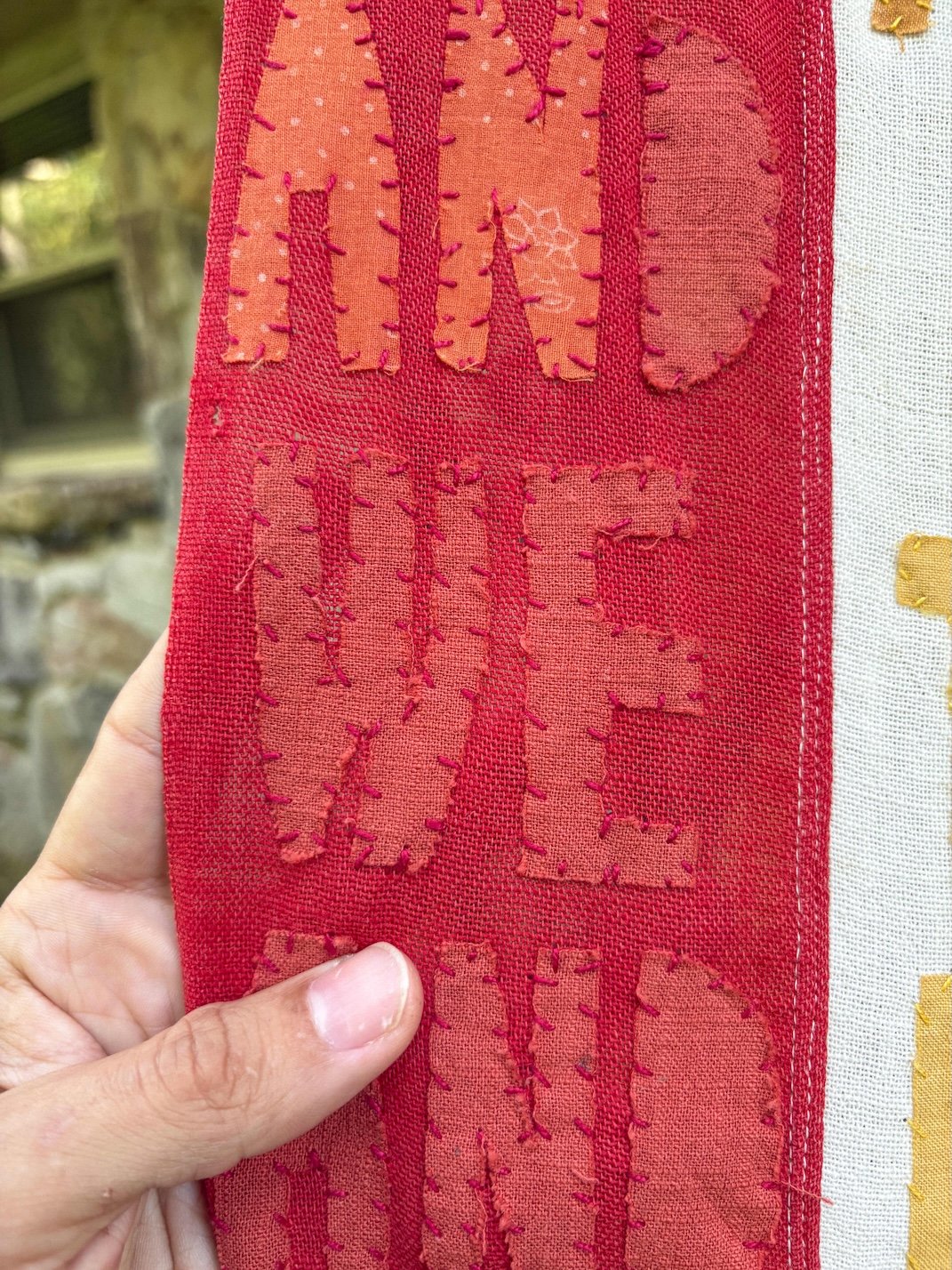

SNAKE HANDLER!

I made this piece in the style of Southern Baptist church banners from my childhood, but the idea came to me as an adult through a dream—an ancestor handing me a writhing poisonous snake, telling me it was the "work of the living" to untangle the injustices of our time. The banner format feels fitting for this message, transforming a sacred visual tradition into a call for accountability. What does it mean to inherit both the beauty and the poison of our family stories?

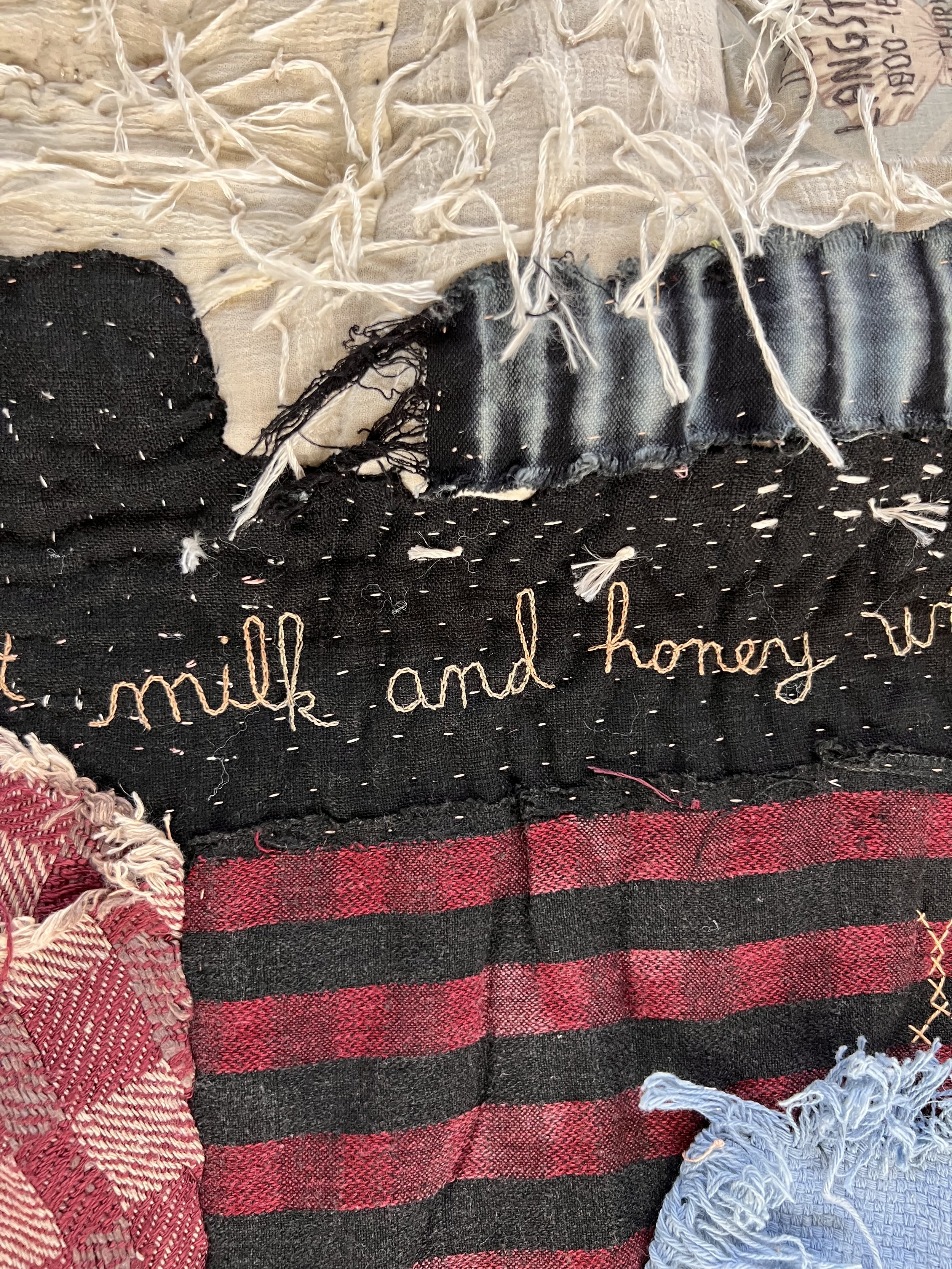

ONUS // ON US

I found this weathered garment in the middle of my neighborhood street, and what struck me most was how you could see every chapter of its lifetime right there—the original cotton color, the bright white bleach, the industrial olive green dye, then where I bleached it again to add my family's Civil War text. To me, this piece works like an alternative calendar, showing how history doesn't disappear but layers on top of itself in our present moment. What would it look like if we could see the accumulated layers of our own stories this clearly?

SILVER DOLLAR

This fan-style genealogical quilt shows how I personally benefit today from the wealth my family accumulated during slavery, tracing two very different family lines that make me a textbook case study in the white American colonial experience. My father's side were subsistence farmers, while my mother's line was far wealthier, enslaving people for generations, and you can see how privilege flows down through the generations by following which branches had access to higher education thanks to their inherited wealth. This inheritance runs all the way to my life today, connecting the opportunities I’ve experienced directly back to those original accumulations.

I THINK WE WOULD KNOW

When I first found records that my ancestors had enslaved Black folks in South Carolina and Kentucky, I asked a family member about it. They quickly responded "no," and then, after a pause, they insisted that surely we would know if they had enslaved people. It made me wonder how many White folks walk around thinking the same things and spurred this entire collection into being.

FAMILY BED

I hand-sewed 36 dolls—one for each slave-owning ancestor and one for me—and piled them all awkwardly into this antique doll bed I found at a local thrift shop. There's something unsettling about seeing us all crowded together like that, but it feels honest about how we're all connected whether we want to acknowledge it or not. I keep thinking about how we can't simply disregard the uncomfortable parts of our family stories when they're still shaping who we are today.

JESSIE TELFAIR & THE WHITE MAN WHO FIRED HER

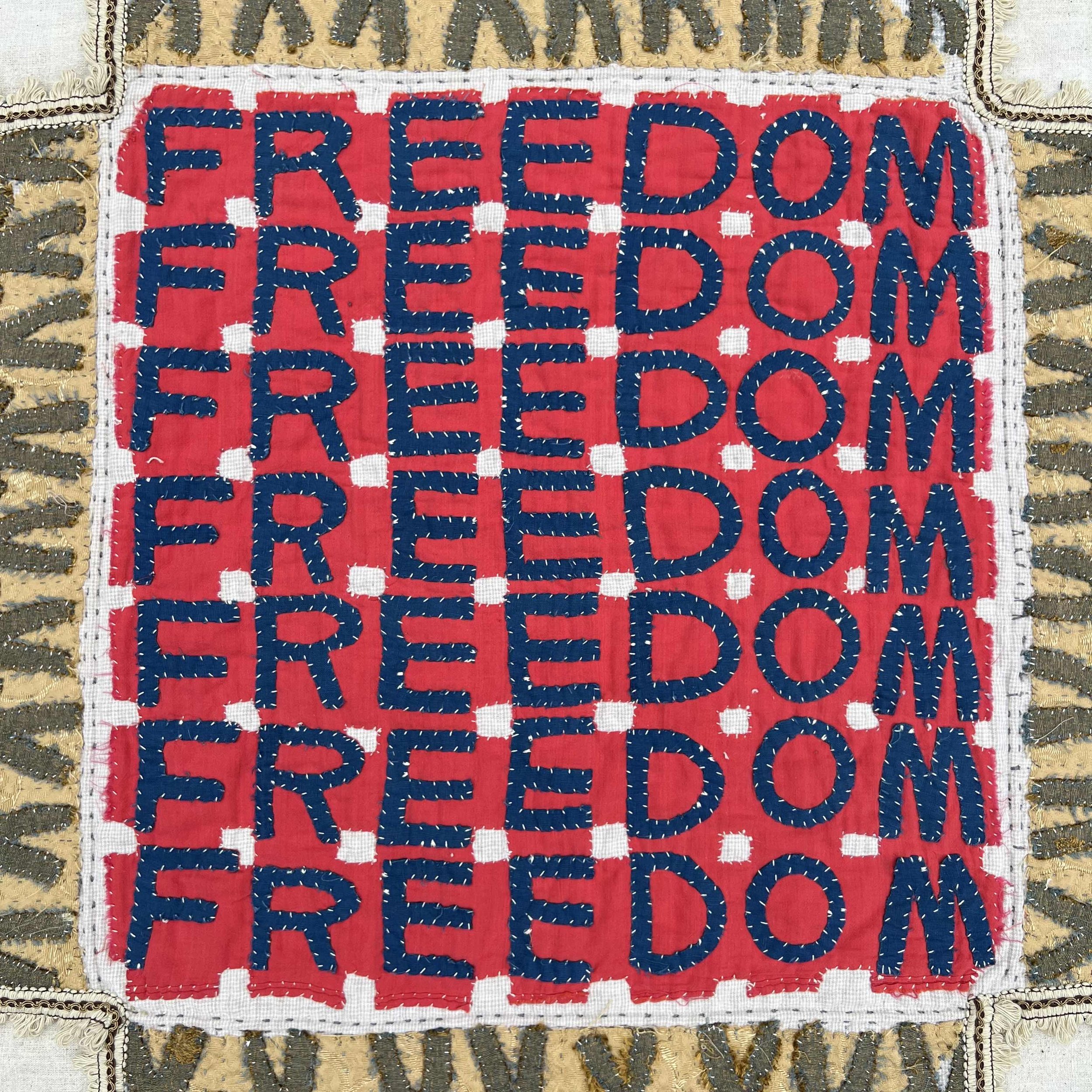

I keep thinking about how family stories travel such different paths through generations—like Jessie Telfair, who was fired in 1963 for registering to vote, then created her iconic Freedom quilts a decade later as a response. On one side of this piece, I celebrate her artistic legacy that the Telfair family rightfully claims as part of their heritage. On the other side, I wonder if the descendants of the white man who fired her even know what their ancestor did. Creating this piece made me realize how differently families curate their histories—some stories becoming legends, others disappearing entirely.

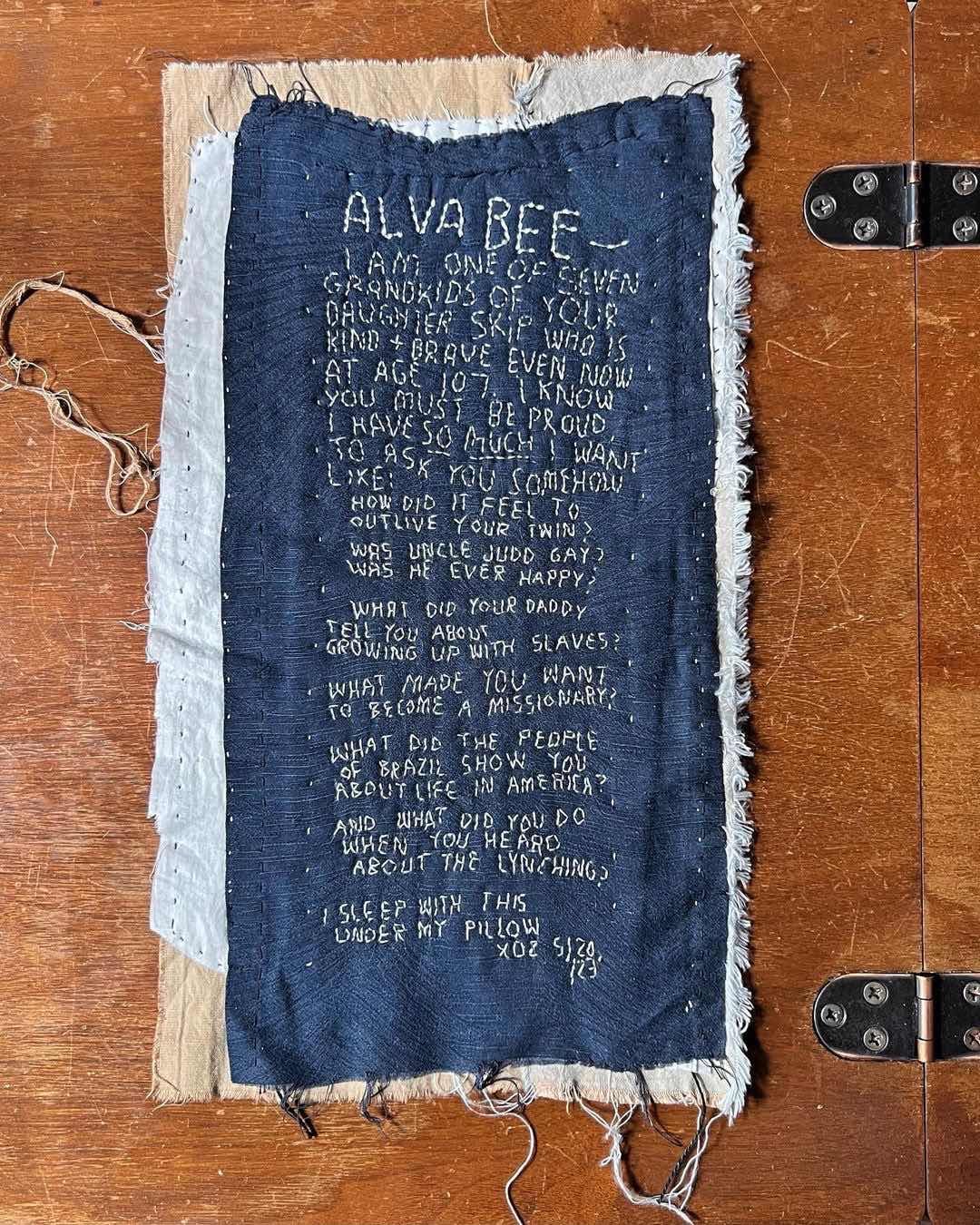

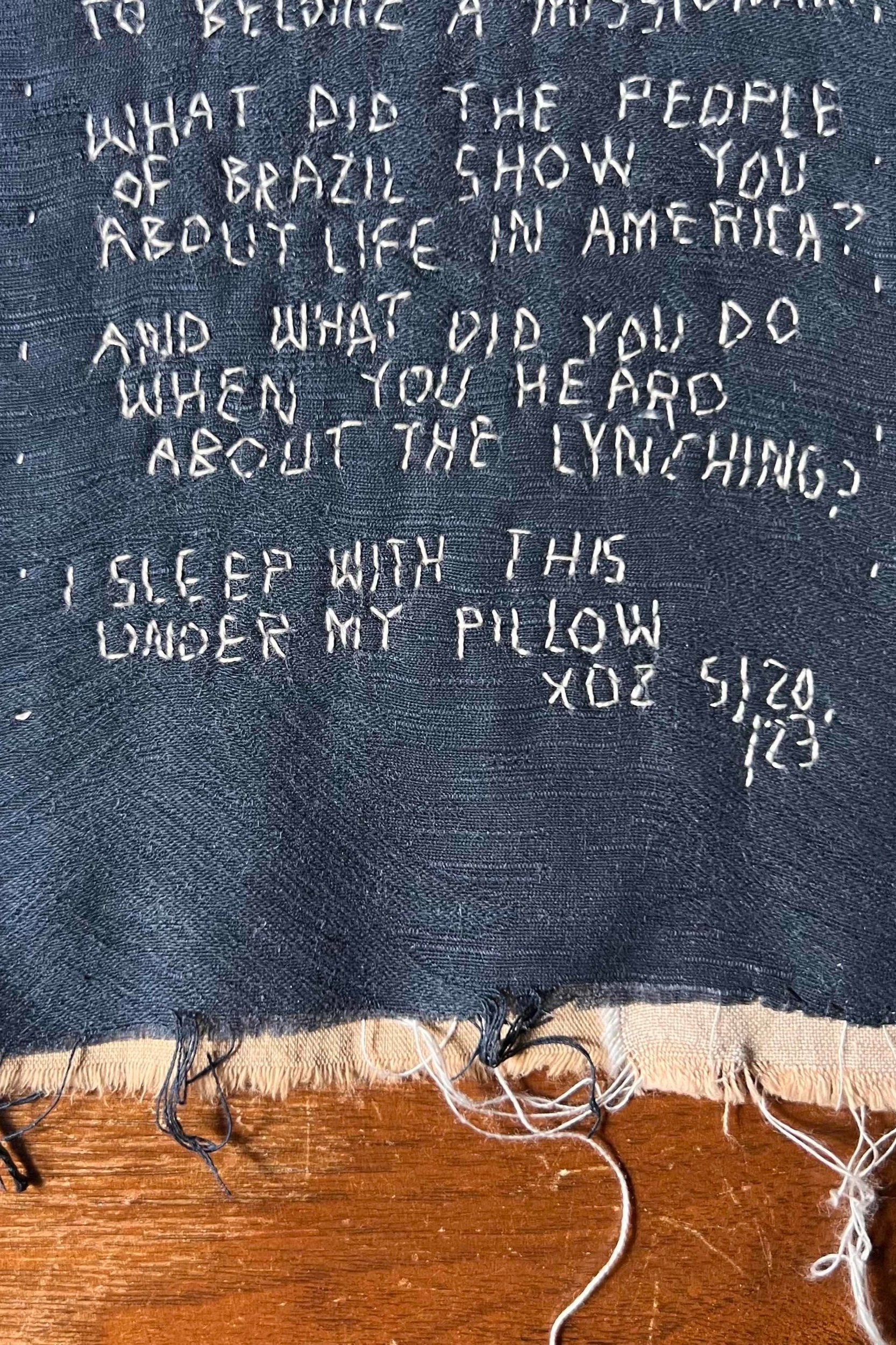

ALVA BEE

I embroidered a letter full of questions to my great-grandfather Alva Bee (whose 1904 class ring I wear everyday) on this small pillow quilt, wishing I could ask him about living through that pivotal post-Civil War generation. I placed this quilt under my pillow, waiting for answers to come through dreams. For the next three nights, responses came and grew so intense, I decided to retire this piece as an oracle and incorporate it into this collection.

GREAT GRANDMOTHERS

This antique quilt from the 1800s has stitched into it the labor and stories of women whose names I'll never know, yet their handwork felt like a thread through time to me. I found myself wondering what would happen if I could sit with my own great-grandmothers and ask for their guidance? What wisdom might emerge from that conversation, and how might their voices help navigate these complexities we've inherited?

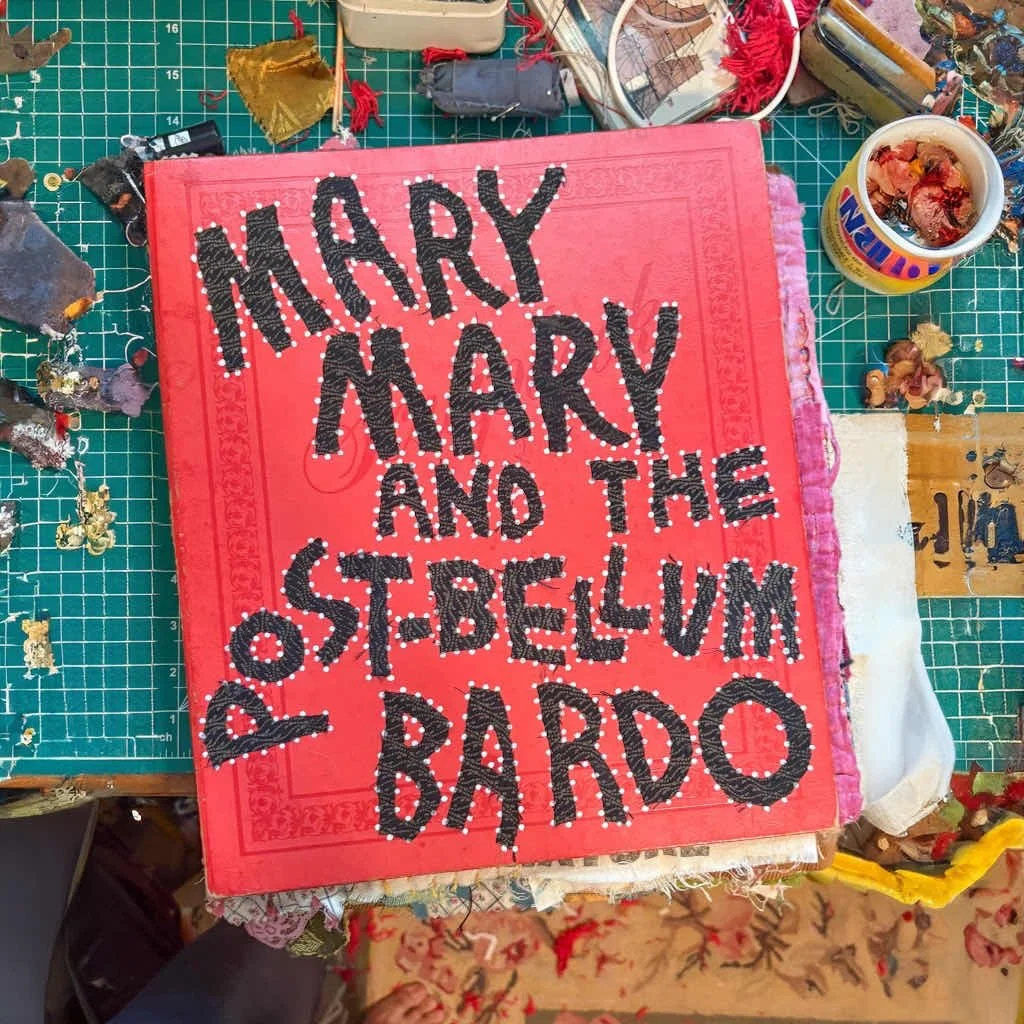

MARY MARY + THE POST-BELLUM BARDO

The familiar rhythm of a childhood nursery rhyme weaves together voices across generations, documenting an imagined conversation between the artist and five matriarchs in his family whose prosperity was built on the labor of enslaved people. Within the artist's personal cosmology, these ancestors—regardless of their earthly choices—now work actively from the other side through their descendants to help correct the wrongs they committed while alive. The juxtaposition asks us to consider how we reckon with inherited stories and whether healing can flow both backward and forward through time.

SAME POISON DIFFERENT BOTTLE

As you turn the crank, you activate new spiritual transmissions—urgent messages ancestors might deliver to us today. Inspired by Victorian-era "crankies,” this piece offers a counterpoint to the silence found in 209 LETTERS, a collection of the artist’s family's Civil War letters that never once mention slavery or Black people. The artist created this piece to give these ancestors a chance to respond from the grave, imagining what they might say if given the opportunity to speak truthfully about their role in supporting slavery. The work invites you to consider: what would honest ancestral accountability sound like, and how might it guide our present moment?

BROAD STRIPES // BRIGHT STARS

I spent months hand-stitching over 1000 letters onto this antique 48-star flag, creating what I can only describe as a careening, breathless thought experiment about American history. The text moves at the speed of my own racing thoughts as I sit with our country's contradictions—the beautiful promises alongside the devastating failures. It seems we're rarely taught that we can simultaneously love a place and be critical of it.

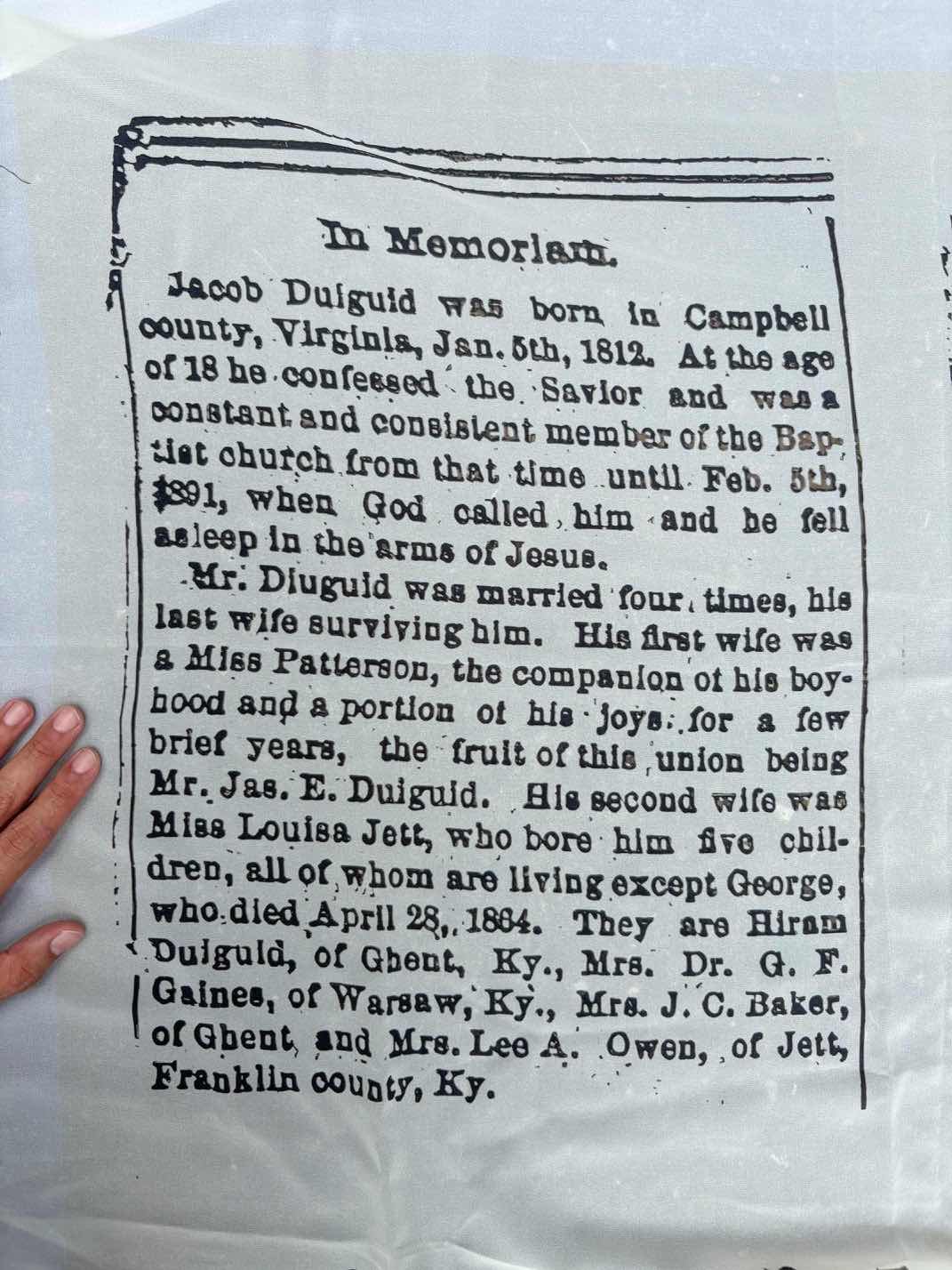

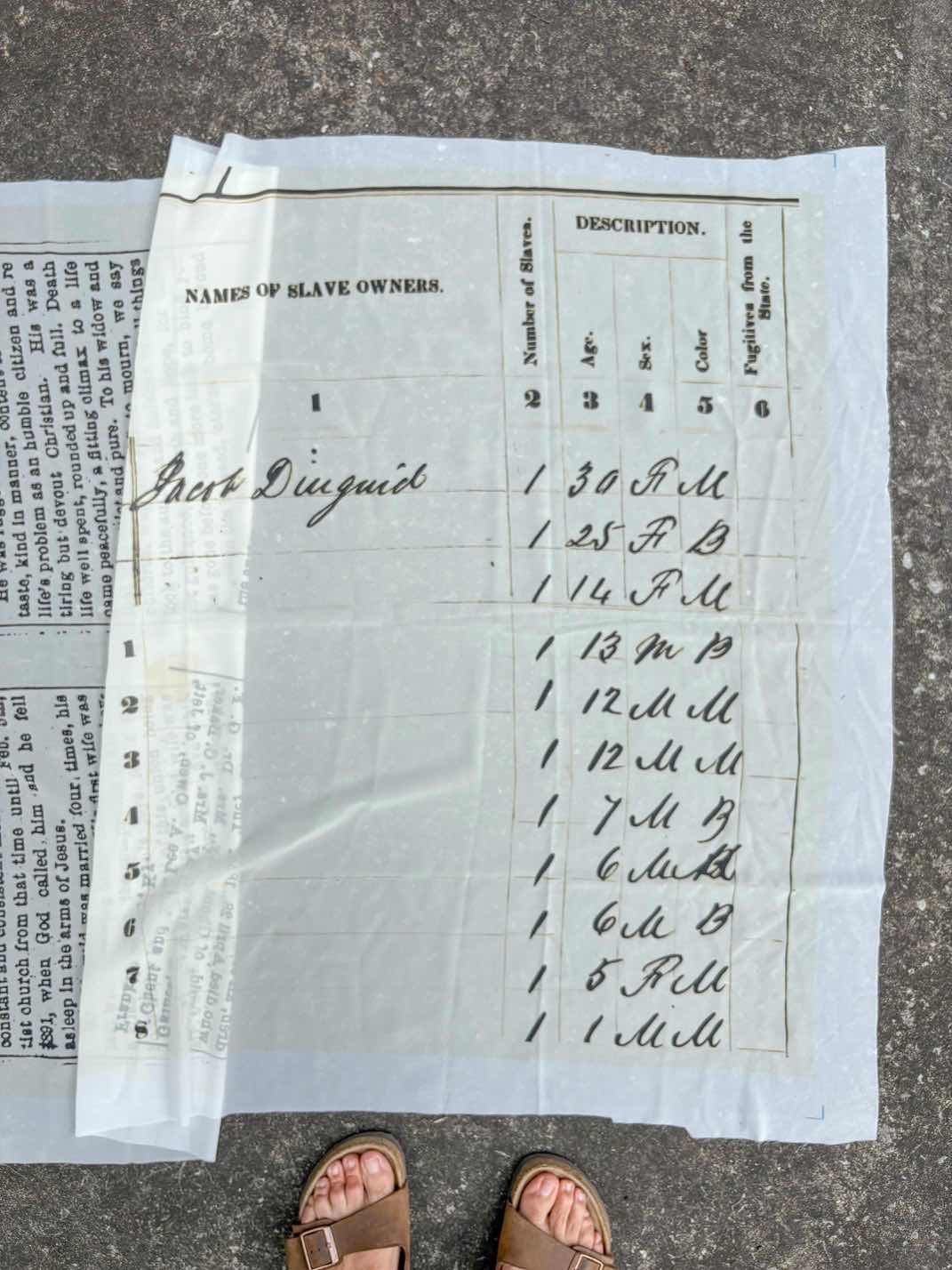

A FITTING CLIMAX

Two documents from my third-great-grandfather tell completely different stories about the same man—a glowing obituary celebrating his Christian devotion alongside an 1860 census coldly listing the eleven people he enslaved, seven of whom may have been his own children. How do we make sense of ancestors who seemed to live with such contradictions?

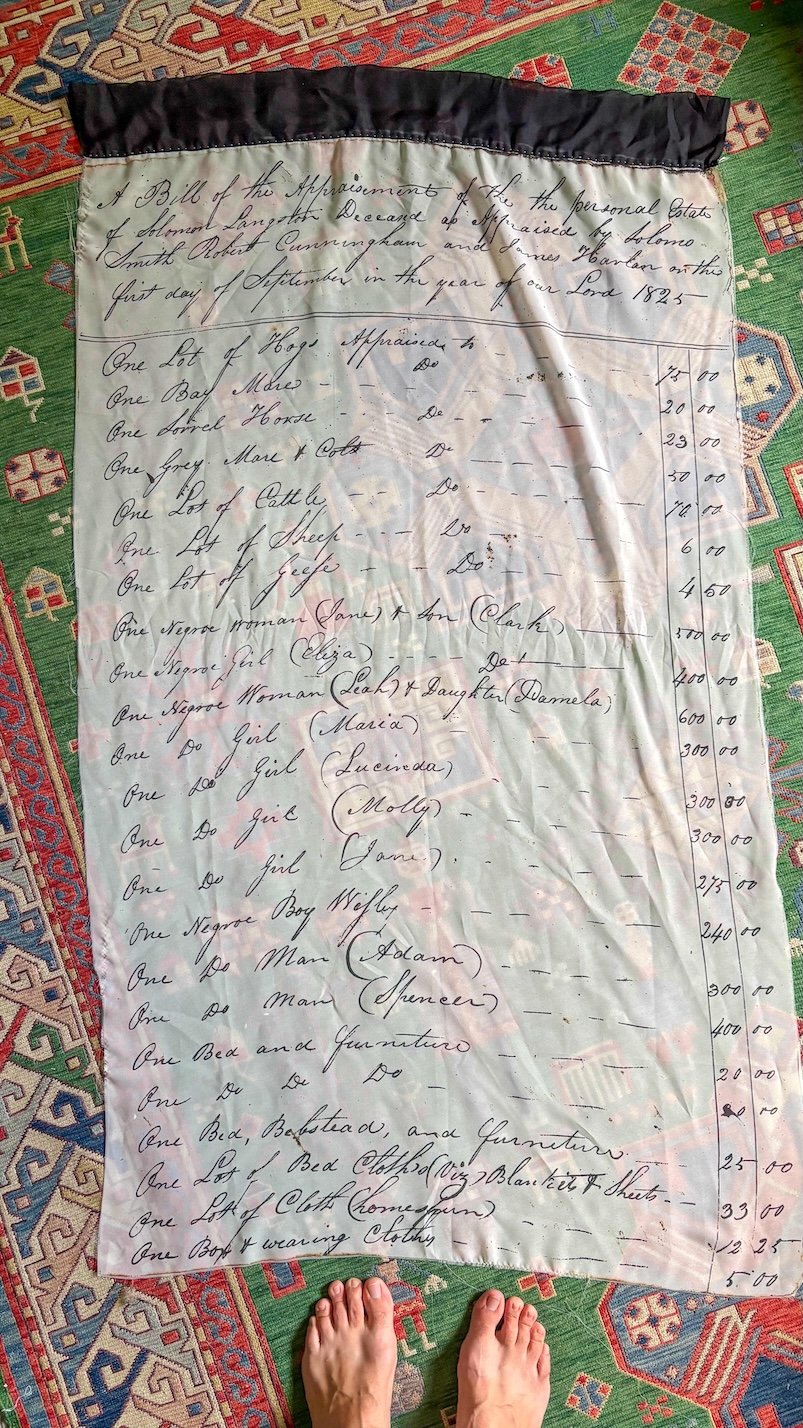

APPRAISEMENT

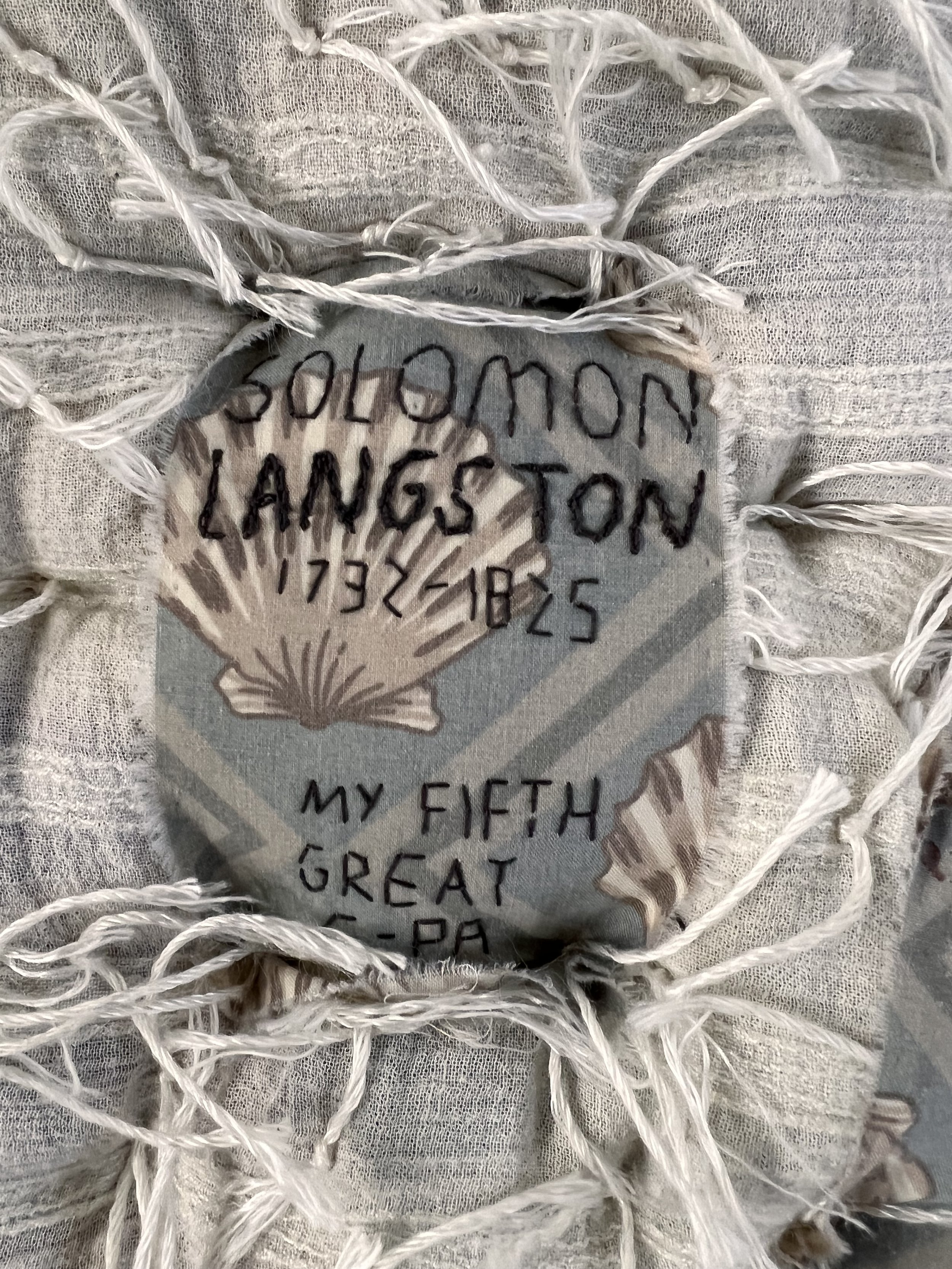

Between the listings for hogs and homespun cloth, you'll find twelve human beings reduced to dollar amounts on this 1825 estate document from my fifth-great-grandfather. How do we hold the weight of knowing that our family's prosperity was built on such casual violence? This inherited wealth didn't disappear—it shaped generations that followed, including my own life today.

209 LETTERS

My family's inherited trove of Civil War letters reveal something unsettling—these poor farmers from North Carolina supported slavery through their Confederate service, yet their correspondence never once mentions slavery or Black people. How do ordinary people participate in systems of harm while staying silent about what they're really doing? What might we be overlooking in our own inherited stories?

YOUR GREAT-AUNT DICEY

Growing up, I heard countless stories about my fourth-great-aunt Dicey Langston—a Revolutionary War hero who ran through darkness to warn her brothers of danger. What those stories never mentioned was that she also enslaved people. How do we honor our ancestors while holding them accountable for the harm they caused?

JANUARY RIVER

[MORE IMAGES SOON] I projected animated family photos onto this antique quilt where I've sewn my own portrait, watching my ancestors' AI-enhanced faces come alive across my own image. In this 8-minute sequence, some of these family members were enslavers or descendants of enslavers, and others have no direct connection with slavery. There's something unsettling about that anonymity, how it mirrors the way whiteness as a whole carries responsibility for historical harm regardless of individual participation. Click for video

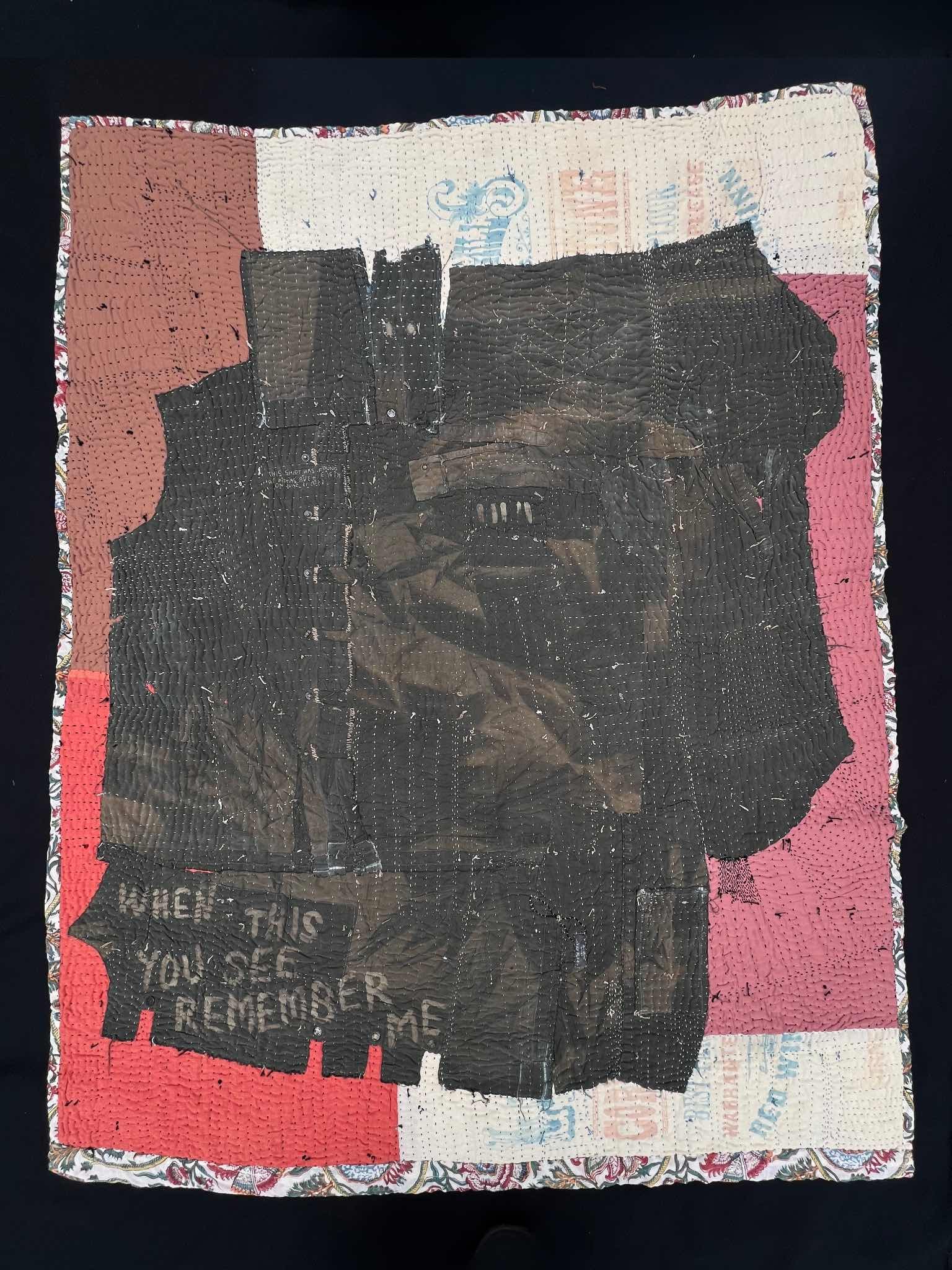

REPARATION QUILT

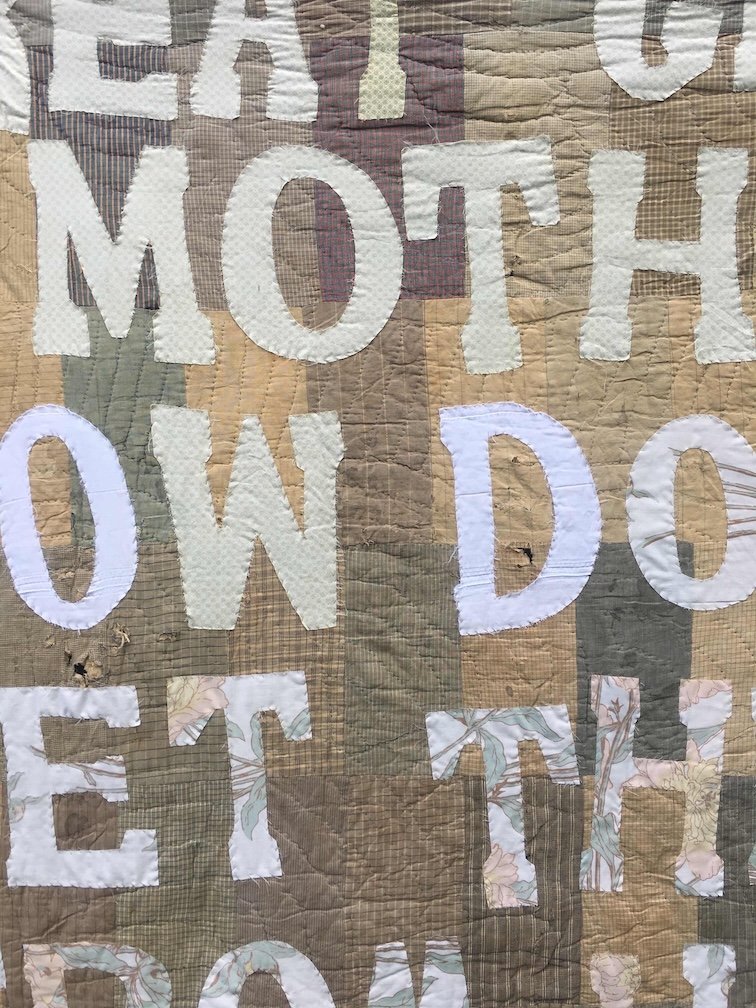

I found this old quilt one late night on eBay and felt an immediate pull to repair it. There's something about old tattered quilts that seems to call out for mending, regardless of how they got that way, which got me thinking about social repair and whether the impulse works the same way. This is an ongoing project that will be displayed in whatever condition it's in when the show opens.

FUTURE PIECES:

TOGETHER FOREVER, a collaborative quilt with my extended family about our inherited wealth

a quilt featuring Tom Bennett Langston: the lone abolitionist in our family

a collaborative quilt with members of my extended black family that we only know about through AncestryDNA

a quilt featuring Mary King, a Black woman who appeared to have had a long-term committed relationship with a White great-uncle of mine

a quilt connecting slave ownership and higher education

a quilt featuring John Avery Foster: first Black deputy sheriff in NC in 1965

a quilt featuring a line from my 5th-great grandfather’s will: the phrase bequeathing slaves to his children, “to him and his heirs forever”, which directly implicates future generations in the fight for racial justice

recreation of the old Stone House an ancestor of mine build designed to withstand defensive attacks from local Saura people in North Carolina

Click here for curator page